6/03/14 (Reposted)

Silver City Adventures©2009

By Alan J. Chenworth

Over the years, I have developed a great love for Silver City, Idaho. It is a beautiful town situated in south-west Idaho, west of Mountain Home and only about 20 miles from the Oregon border. Silver City, as a town, is only inhabited during the summer months. There is no power, no paved roads and no access during the winter months—unless you like to snowmobile. The original hotel and bar remain open during the summer months; along with one or two other small stores or gift shops. These businesses, along with the rest of town, remain in a state of arrested decay. The original church is still there, and it is used for community services during the summer months, and the old school house now holds a small museum. No new structures are allowed in town. It is a fantastic place to visit.

The Silver City church is still in use (occasionally).

Silver City got its start in about 1863, when gold was discovered in Jordan Creek. Between 1863 and 1864, about 4 million dollars in gold and silver was taken from the creek. Silver City is so named because of the large amounts of silver found there—between 20 and 100 oz silver for every ounce of gold.[1] Even the placer gold is only about 49% gold!

The mines were worked continuously until 1942 when the War Act closed the mines. The copper wires were pulled out and the town was largely forgotten.

The first time I visited Silver City was in 2000. I set up a dredge below Ruby City (just N. of Silver City). After several days in the water, I had about ½ ounce of amalgam—and was very excited. It seemed I had paid for my trip. After burning off the mercury, I discovered that I had nearly ½ ounce of silver—yes there was a little gold in there, but not enough to pay for the gas to get there. It seems that there had been a mill there at one time, and they lost a lot of silver and mercury. If I had more than one dwt. of gold, I would be surprised. As a result I did not return there for many years.

An old brewery in Silver City.

An old brewery in Silver City.

By 2005 I had joined with a club that had some claims on Jordan Creek. After hearing many success stories, I decided to give it another try. I purchased an Idaho State dredge permit and waited for Memorial Day (dredging is allowed year round, but there was no access until the snowplow opened the road for Memorial Day weekend).

The temperature had been in the low 80’s for several weeks when I loaded up my truck, and things were looking good. A storm had been forecast to hit over the weekend, but I figured with 5 days in Silver City, I should still have 3 or 4 days of good weather. I could not have been more wrong.

I got to Silver City late Friday night (OK, it was 2:30am Saturday morning), and the first few snowflakes began to fall as I pulled into the campsite. When I got up Saturday morning, there was 8 inches on the ground and it was falling fast. In all, it snowed for 3 days, then was cold and overcast the fourth. The river came up about a foot, and even if it hadn’t, it was too cold to dredge.

With all the snow, dredging was out of the question, so I prepared to sluice.

When I go dredging, I always bring along a sluice and shovel, just in case something happens—such as when my dredge breaks down (it is about 20 years old), or the weather doesn’t cooperate. In this case, I grabbed my 6” sluice (a Gold Saver Sluice from the Roaring Camp Mining Co.), a five gallon bucket, and my shovel—and headed up the hill. I found a small side stream that showed some color, set up and went to work. In an hour’s time, I had found about a pennyweight of gold. The gold looked good, but I was drenched to the bone and taking a chill. I could see the early signs of hypothermia, so I headed down the hill to my camp. I returned the next day, only to lose my snuffer bottle. After looking for the bottle for several hours, I gave up the search and got the sluice back in the water—with results similar to the previous day. As it was still snowing, I only worked for a few hours.

The next day, the snow eased up late in the afternoon, so I drove around to the top of the gulch and hiked down. I found a likely looking spot, set up my sluice, and went to work. In the last two hours before dark, I pulled out about two dwt. Not bad.

My fourth day there, I attempted to dredge—and even managed to get a hole to bedrock—but it was just too cold, and I finally gave up. After putting the dredge away (and warming up), I returned to the small side creek and worked by sluice for another hour. I didn’t do as well as the previous days, but did still pull out most of a dwt. The sun finally came out the next day as I was packing up camp and driving home. In all, I pulled out around ¼ oz of gold in about 5 or 6 hours of sluicing—and vowed that I would return the next year when the weather was better.

I did return the next year, and the weather was great—unfortunately, I woke up sick as a dog, and did almost nothing until the day that I was supposed to leave. I did watch some friends of mine do quite well in Jordan Creek though.

You know what they say, “The third time is the charm.” With memories of the gold haunting me, I headed back to Silver City in 2008 for a four day weekend. I had my dredged packed and was eagerly waiting to see what the river had for me.

Just my luck—another storm—it snowed the first day and rained the next two. Again, I grabbed my back-up sluice, and headed up the canyon. By now, I knew a little about the area. In order to see what the canyon really had to offer, I began to carefully sample my way up the creek. It took about an hour before I settled on some shallow bedrock that seemed to pay much better than the rest—the first sample pan had about 50 colors, and the second was just as good. It was here that I set up my sluice. I worked about 6 hours and cleaned out a small pocket with about ½ oz of nice clean gold. Not too bad.

The next day I returned and pushed up the creek. The gold had tapered off some from the day before, but by mid-day, I had worked up into another, even better, pocket. Again I pulled out about ½ ounce of gold, including a small nugget and a nice piece of 3-d wire-gold. The wire gold was three strands that were joined at both ends, but bowed out in the middle, similar to the top of a steel baluster. It was beautiful.

By the third day, the weather had eased up, and I thought I would try dredging. I set up my dredge in a quiet spot in the river, and went to work. After dredging a hole about four feet deep—without hitting bedrock—I started to wonder what I was doing. I had a spot in the gulch that was paying about ½ oz per day, with easy work—where I could stay warm and dry—and I was dredging in a cold river in the late spring, when the river was too high and the temperature was too cold—and I wasn’t getting anywhere near as much gold as I had been. I figured I must be crazy.

As soon as I finished off the first tank of gas, I pulled out of the river, dried off, and headed back up the gulch. I was able to pull another ¼ ounce of gold out of the river that evening.

I left Silver City the next morning with about 1 ¼ ounces of placer gold. It was a good trip—and one that paid for itself, even with gasoline at nearly 5$/gallon.

A productive trip!

As I drove home, feeling content with the ounce of gold in my pocket, I reviewed the trip. I decided that I was productive for two simple reasons: First, I sampled (a lot) before working. Remember, sample, sample, sample. If it isn’t paying, don’t waste your time; move on to a better spot. The second reason I was successful was that I had a back-up plan. In my experience dredges break, parts get lost, weather won’t cooperate, even health may prevent me from dredging—Every now and then, I may need to do something different. Always have a back-up.

The Silver City area is a fantastic place to visit. It is rich in both history and mining, and it is beautiful. And while it has been a very productive district for almost 150 years—working there does have its challenges, especially with the weather. For me, there is nothing worse than taking a long trip, only to have it fall apart when you can’t dredge. I have found that with a little patience and planning, many bad situations can turn quite rosy.

[1] W.W. Stanley, GOLD IN IDAHO, 1946, Idaho Bureau of Mines and Geology, 53 p., Owyhee County, p. 37-39.

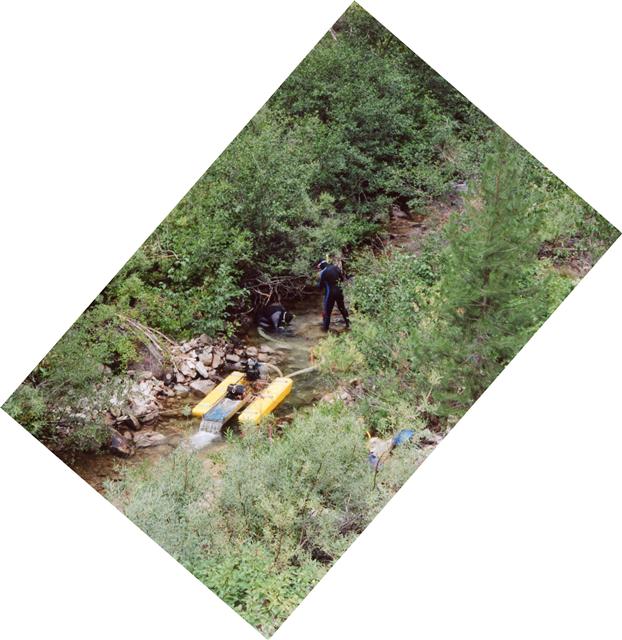

My son and I working a productive high-bar in Wide West Gulch.

The Rocky Bar Mining District©2009

by Alan Chenworth

A goodly portion of my mining experience has been in and around Rock Bar, Idaho, and over the years I have had many wonderful expierences there. I have had some great finds, met some great people, and camped in some the prettiest places on earth—all right there around Rocky Bar.

[i] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocky_Bar,_Idaho, 2009.

[ii] W.W. Stanley, 1968, Gold in Idaho, Pamphlet No. 68, Idaho Bureau of Mines p. 26-28.

How to Classify Your Gold

Here is a new video on classifying your gold. We took over 1 1/2 ounces of gold and classified it into four (4) size catagories. (Sorry it is a bit grainy–it seems the camera resolution was set too low.)

The Bingham Canyon Copper Mine ©2010

By Alan Chenworth

About 30 miles to the south west of Salt Lake City lies the world famous Bingham Canyon Copper Mine. Its products include copper, gold, silver, molybdenite and sulfuric acid. By all accounts, it is one of the richest mines in the history of man (fourth richest, to be exact). It has been mined continuously for more than 100 years—almost 150 years if you count the silver mines in the district around it. The mine is huge. So big, in fact, that when you look at it, you lose all sense of scale. What started out as a large mountain is now a hole that measures about 2 ¾ miles across and more than ¾ mile deep. They have literally moved a mountain.

In the case of Bingham Canyon, about 38 M.A. (Million Years Ago), magma from deep within the earth pushed up through the country rock (mostly quartzite, but with two large limestone units and several marley siltstone beds) and formed a monzonite stock. (Monzonite (MZ) is similar to granite, but with little or no QZ.) Some time later—probably on the order of several hundred thousand years—another intrusion pushed through. This dike was quartz monzonite porphyry (QMP). The intrusion of the QMP locally fractured the host rocks, including the QZ and MZ, allowing the mineral rich hydrothermal fluids from off the QMP to flow through the cracks and fissures in the QZ and MZ. As the hot fluids cooled, they left behind the minerals that they had carried, forming a large, relatively rich copper deposit. The dominant copper minerals found at Bingham are chalcopyrite and bornite. Most of the gold—and all that is currently produced at the copper mine—is found locked up within the bornite.

Shortly after the deposition of the copper, there was another mineralizing event, more prominent at depth, where fluids rich in molybdenite created a second economic deposit. While molybdenite (moly) has long been found in the copper ores, a very large deposit of molybdenite has recently been identified below the copper ore. Molybdenite, which is currently valued at about $18/lb, has long been a very profitable byproduct for the mine, and is used in a variety of industrial applications where among other uses it is used to harden steel and as a high end lubricant.

The geology of Bingham Canyon has become the standard for the porphyry type copper mine. This model includes the zoning of minerals— copper mineralization in the center, surrounded by pyrite, with a lead-zinc halo on the outside. The free-milling gold found in the placers of the district likely originated in the lead-zinc mines around the periphery, where free gold has been noted. Similarly, we find corresponding alteration patterns at Bingham—an argillic/sericitic (clay) alteration—thought to be the youngest alteration—at the center, in and around the intrusive quartz monzonite porphyry. Then we have the potassic alteration halo around it. The potassic halo is thought to be related to the hydrothermal fluids that carried the copper, and includes minerals such as biotite, phlogopyte and potassium feldspar, and a significant increase in copper minerals (bornite and chalcopyrite) can be seen well in these potassicly altered zones. The potassic alteration is surrounded by a larger zone of propylitic alteration. The propylitic alteration was the earliest and largest alteration event, and is seen in the monzonite host rocks of the area. Its dominant minerals assemblages include actinolite, diopside, chlorite and some epidote, as well a fair bit of magnetite. The two large limestone units have also been large contributors to the mines copper production as they were altered to skarn mineral assemblages. These skarns range from wollastonite/marble to garnet to massive sulfides. These skarns also include relatively high percentages of chalcopyrite, bornite and gold.

It may be hard to believe, but the now famous Kennecott Copper Mine at Bingham Canyon, Utah had a rough and rocky start. It has one of the most unusual histories in modern mining. In fact, it is the mine that almost wasn’t.

Most western mining districts started with the discovery of placer gold. As the placers were developed and worked out, prospectors turned their attention to the load deposits from which the placers were formed. Bingham was, in fact, backwards. It was the load deposits (silver-lead veins) that were found first, with attention turning to the placers some time later.

Ken Krahulec of the Utah Geological Survey has done a tremendous job in compiling the history of Bingham Canyon, which he published in a Society of Economic Geologists paper entitled: History and Production of the West Mountain (Bingham) Mining District. The following paragraphs describing the discovery and development of Bingham Canyon should be attributed to him.[1]

t

Erastus Bingham and his sons were Mormon pioneers that came west with Brigham Young and settled with him in the Salt Lake Valley. In 1848, they settled the mouth of what is now Bingham Canyon with a small ranching operation .

While working on the upper slopes of the canyon, the Bingham’s found some rich specimens of galena, a lead ore that is often rich in silver. They excitedly took some samples and headed for Brigham’s place. Upon seeing the samples, Brigham Young told him to leave the minerals alone, instead encouraging the people to focus on farming and the industries that the people in the Salt Lake Valley would need to survive.

The Bingham’s stayed in the canyon for several more years, waiting for the chance to get back to their prospects. In time, they moved to settle the Ogden area, and the mineral discovery was forgotten.

In the 1860’s, Colonel Conner arrived in Utah with a contingency of troops that had come largely from the goldfields of California. He was charged with putting down the Mormon problem, and figured that the easiest way to do that was to make a large mineral discovery and let the flood of prospectors dilute the Mormon population. In their off-duty hours, he encouraged these prospectors to search the local hill for minerals. This policy led to the discovery of several large ore-bodies, including Alta and Bingham Canyon.

In the fall of 1863, George Ogilvie re-discovered the silver rich galena on the slopes above Bingham Canyon while logging on the high slopes, and the rush was on. The West Mountain Mining District was formed on Dec. 17, 1863. This area was very remote, and according to Heikes[2], the area mines were not well developed for several years due to both a lack of transportation and a mill to reduce the ores. It wasn’t until 1868, when the railroad came to the canyon, that the first carload of copper ore was sent to be processed.

Even with the railroad, the mines struggled. The area had “vast reserves of very low grade copper,”[3] but it was of too low a grade to profitably mine. The profitable copper mines of the day generally worked ores containing 10-15% copper—or greater—while the ores of Bingham Canyon contained only 2% copper. Most of the lead-silver mines had the same problem. They just could not work the mines economically.

It was not until 1896, when the Highland Boy mine began working a high grade vein, that there was any significant copper production in the Bingham Canyon area. In 1899 Daniel C. Jackling released a study showing that the copper could be mined profitably if the production levels were increased dramatically above what was currently being done in the underground mines. He proposed using large steam shovels to work the low grade (about 2%) ore in an open pit mine, and locomotives to haul the ore to a crusher. He convinced the Utah Copper Company to invest in his ideas, and open pit operations began. In 1906, the Boston Consolidated Mines opened their own open pit mine, following the lead of the Utah Copper Company. By 1910, it became apparent that neither the Utah Copper Company nor Boston Consolidated Mine could continue to grow because of the other. There just wasn’t room. [4] They merged, forming the company that would latter become the Utah Copper Consolidated Corporation. In 1936, Kennecott Copper bought out Utah Copper Consolidated, and formed the Kennecott Utah Copper Company.

Interestingly, Mr. Jackling had also approached the president of General Electric about investing in his mine, since GE was a large user of copper, and they were looking to gain control of a good source of copper. It is said that the president of GE—after looking at the reserve numbers of the Utah Copper’s Bingham Canyon Mine—could not accept the numbers as credible, they were so large.[5] He walked away . . . big mistake!!!

As the mine continued to grow, technology was able to lower the cost of production and expand the mines reserves. The railroad hauled the ore until it was replaced in the late 1970’s with large haul trucks. An in-pit crusher was installed, making a conveyor system feasible. A tunnel was cut, and a three mile conveyor built to run from the crusher, through the tunnel, and across Copperton to the mill. A large pipeline was also installed to move the copper concentrates the 18 miles from the Copperton Mill and Concentrator to the smelter at Magna. All of these improvements allow the Bingham Canyon mine to operate at an average ore grade of about 0.6% Cu. By 1981, Kennecott Utah Copper was struggling due to low copper prices and sold out to Standard Oil. In 1986, Standard Oil built a new mill and concentrator just outside of Copperton, at a cost of about $350 million. BP bought all of Standard Oils holdings in 1987. Rio Tinto, the current owner, bought it from BP in 1989. In 1995, Rio Tinto invested $880 million to build a new smelter. This new smelter is the cleanest and most efficient smelter in the world.

Rio Tintos’ Kennecott Copper Mine produces an estimated 13% of all the copper used in the US. In fact, according to the USGS, the Bingham Canyon was the largest producer of copper in the US during 2009 with 25% of all us production.[6] (Before 2009, it has held the number two spot behind Freeport’s Morenci copper mine for several years). It has been so important to prosperity and security of the United States that during World War II, it was producing as much as one-third of all the copper used by Allied Forces.[7]

While the current mine plans forecasts an end of mining in about 2019, Bingham Canyons’ future remains bright. Company officials are looking at an expansion, that if approved, will extend the mine life until about 2036. There are also several possible opportunities for underground mining—both in some rich copper-gold skarn deposits on the north side of the pit, as well as the deep molybdenite that has been evaluated for possible block-cave mining methods. Currently, they are also building a $270 million autoclave at the Copperton Concentrator to process the molybdenum and rhenium recovered from its flotation cells.

The silver-lead-zinc mines around the outer edge of the porphyry had fortunes similar to the copper mining. With advances in transportation, machinery and other technology at the turn of the century, the silver-lead-zinc mines in the district were able to operate at a profit. The Lark and US Metals mines were able to work through out most of the 20th century, with the Lark mine closing in 1971. Interestingly, it was not the lack of available ore that closed the Lark Mine. When it closed, it still had some very profitable ore in reserve—instead, it closed because of new environmental regulations that forced the company to shut down its smelter. Because they had no smelter, and it was too costly to ship the ore to the few remaining smelters for processing (out of state and/or out of the country), they were forced to shut down the mine. (Much of the silver-lead-zinc industry has the same problem today. You can find and mine a profitable deposit, but will be forced to send the ore out of the country to be processed—typically making it unprofitable). Anaconda also worked the copper-gold skarns found underground to the west of the copper mine in the 1980’s. The Kennecott Copper Mine has since bought out all these underground mines, including the Lark, US Metals, and Anaconda.

The gold placers were discovered in 1864, one year after the discovery of the argeniferous galena. It is not known who discovered the placers, but their discovery is what fueled the early development of the canyon. In fact, in the early days, the only profitable mines in the canyon were the placer mines. Copper nuggets were often found in the creek, but because copper only sold for about 12 cents a pound, it was often considered a nuisance and thrown aside. [8]

Between 1864 and 1871, more than $1,000,000 in gold was pulled from the canyon, and another $500,000 between 1871 and 1920 (figured at $35/ounce).[9] Because many of the placers in the canyon were buried under deep overburden, many of the placer mines were underground drifts along the bedrock. The gold placers were found in a rusty red, iron stained pay layer just above bedrock. Much of the gold was also stained red from the iron staining, and black nuggets were not uncommon in the district. The gold is of a fairly high karat, running about .890 fine. There are still some deep placer deposits in and around Bingham Canyon, such as those at Bear Gulch, that could be worked economically if they weren’t buried under hundreds of feet of waste dump. Bingham Canyon was by far the richest placer in Utah, and the only major placer camp in the state.

At the junction of Dry Fork and Bingham Canyon—at what was probably the richest placer claim in the area—Pete and Dan Clay were able to mine about $100,000 dollars of gold. This total includes the largest gold nugget ever found in Utah, which weighed in at 7.75 ounces.[10] There is still gold mined Bingham Canyon, only now it is load gold that is mined. Even with the low grade of gold in its ores, Bingham Canyon is still a major gold producer—producing over 550,000 Troy ounces in 2009.

The towns that grew in Bingham Canyon also had an interesting history. With the discovery of galena in 1863, the Bingham area was soon blanketed in claims—and Bingham Canyon quickly grew to be one of the largest cities in the state. Bingham Canyon (town) was also known as the longest city in the state, being (for the most part) one street wide and 5 miles long. Other towns also sprang up in the canyon, both above and below Bingham Canyon, from Leadmine (Frog Town) that supported smelters at the bottom of the canyon to Highland Boy, supporting the Highland Boy Mines in the Silver-Lead district on the slopes high above the canyon. High above the canyon, on the other side of the mountain, was the town of Galena, among others, as well as the railroad town of Dinkieville.

It was interesting to note that during most of the 1860’s and 70’s, raw sewage from the homes and business in Bingham Canyon was dumped directly into Bingham Creek, yet there was no problem with odor or disease. In fact, the stream ran clear and clean looking. The copper sulfides dissolved in the water acted as a disinfectant, killing all of the bacteria.[11]

Like its beginnings, the demise of Bingham Canyon city was also backwards. Most mining towns die when the mines play out—but Bingham Canyon died when it was discovered its rich ores were located beneath the area towns. One by one, the mine gobbled up the towns as it continued to grow. First went Galena and Highland Boy, then Carr Fork. By 1971, the mine was at the foot of Bingham Canyon (town). The town was dis-incorporated, sold, and by 2000, had been completely buried under a thousand feet of waste dump.

With the exception of Leadmine, which has a bar and 3 houses that survive, all of the towns in the canyon have been either mined away or buried under a thousand feet of waste dump. Copperton is the only surviving copper camp. It was built at the mouth of the canyon in the 1920’s as a place for the company’s management to live.

The Bingham Canyon mine is one of Northern Utah’s biggest tourist attractions. Every year between April and October, Rio Tinto operates a Visitors Center and Museum. The Visitors Center overlooks the mine and has exceptional samples of the regions minerals, maps and histories. There are photos and videos documenting the rich history of the now deceased towns. Next door, the Copperton Lion’s Club operates a small gift shop. Rio Tinto charges $5 per car to visit the mine ($25 for mini-tour busses and $50 for the full sized ones. According to Kennecott’s website (http://www.kennecott.com/), school buses, veterans groups, Boy Scouts in uniform and county senior citizen programs are let in at no charge. ALL of the proceeds are donated to local charities.

[1] Krahulec, K., History and Production of the West Mountain (Bingham) Mining District, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Oquirrh Mountains, p. 189-217.

[2] Butler, B.S., Laughlin, G.F., and Heikes, V.C., The Ore Deposits of Utah, 1920, USGS Professional Paper 111, p. 341-362.

[3] Strack to move a mountain

[4] “

[5] Krahulec, K., History and Production of the West Mountain (Bingham) Mining District, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Oquirrh Mountains, p. 189-217.

[6] Daniel Edelstein, USGS, written communication, April 2010

[7] Internet, June 2010, http://www.kennecott.com/educators/mine-facts/

[8] Treasure House: The Utah Mining Story, Video, 1995, Groberg Communications, Bountiful Utah.

[9] Johnson, MG, Placer Deposits of Utah, 1968.

[10] Bailey, L.R., Old Reliable—A History of Bingham Canyon, Utah, 1988, p. 18-19.

The placer mines in and around Rocky Bar also have a long and varied history. The first miners came in and worked the easily accessible placers—working both the creek bottoms and the numerous high bar deposits found along the creek. A high bar deposit is formed when a creek or river cuts a river valley, depositing its gold bearing materials on the bottom of the valley. The river then cuts a new, more narrow river valley, leaving remnants of the old river valley high and dry. On large river systems, high-bar deposits can be found hundreds to as much as a thousand feet above the current river elevation. Often as not though, the high bars are found tens to a hundred feet above the current river elevation. This is especially true on small river/creek systems. I don’t have production numbers on what these early placer miners found, but given the extensiveness of the workings, what they found was substantial. When the Anglo miners finished up, the Chinese came in and re-worked many of the areas. Some neatly stacked rows of rocks indicate their workings.

![Bingham P7[1]](http://goldpanningutah.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Bingham-P71.jpg)

![Bingham P8[1]](http://goldpanningutah.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Bingham-P811.jpg)

![Clipper Ridge P5[1]](http://goldpanningutah.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Clipper-Ridge-P512.jpg)

![Bingham P3[1]](http://goldpanningutah.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Bingham-P31.jpg)

![Bingham P10[1]](http://goldpanningutah.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Bingham-P1012.jpg)